育休? 俺達には関係ないワンと言ってるかも。

Our members’ beloved dogs, Moko and Mame, gaze at the sunset over the Sea of Japan.

“Paternity leave? That’s got nothing to do with us, woof!” they might be saying.

まぁ、聞いてください。Well, hear me out.

男性の育休必要ですかなんて言うと今のご時世四方八方から罵声浴びせられそうだし、袋叩きにもあいそうです。あなたは女性の子育ての大変さがわかってるの?あなたは子育てなんてしたことないんじゃないの?と問い詰められること間違いありません。

実はわかりすぎるほどわかっているつもりです。

これは、制度として必要なのかなんですよね、なんかこれみよがしなタイトルにしちゃいました、すみません。

とまれ、本題です。

今の子育ては、世帯人数も少なく実家も遠ければ、その重荷はお母さん一人の背中に重くのしかかっているのがその実情でしょう。いわゆるワンオペ子育てですね。

これは全くのかかりっきりでたまの息抜きもできません。

その子どもが体調崩したら大変です、一人で病院に連れて行かなきゃいけませんが運転は無理、タクシーは高い。どうすりゃええんじゃーとなるでしょう。

そんな状況で育休取ってるお母さんは自分のキャリアに対する焦りもあったりするでしょう。

女性が1人で子供育てるのってめちゃくちゃ大変ですよ(分かったような言い方になってます、お気を悪くされたらすみません)、ぜひ男性の方は寄り添ってあげていただきたいと思います。

男性の育休必要ですかというのは、制度として必要なのかと言うことなんです。

制度として、“会社休んでいる間は国が会社に代わって給料を出すからサラリーマンのみなさん会社は安心して休んでくださいよー”っていう、そういう制度が必要なのかという意味なんです。

Saying something like “Do we really need paternity leave?” in this day and age is bound to invite criticism from all sides. I’d probably get yelled at and torn apart with questions like, “Do you even understand how hard it is for women to raise children?” or “Have you ever experienced parenting yourself?”

To be honest, I believe I understand these challenges more than enough.

The real question I’m trying to raise here is whether this needs to exist as a system. I know the title sounds a bit provocative—sorry about that! Anyway, let’s get to the point.

Today, with fewer people living in each household and families often living far from their extended relatives, the burden of childcare tends to fall entirely on the mother’s shoulders. This is what’s often called “solo parenting.” It’s an all-consuming task, leaving no time for a break.

Now imagine the child gets sick—what happens then? The mother has to take them to the hospital, but she can’t drive, and taxis are expensive. It’s a situation where she’s likely thinking, “What on earth am I supposed to do?”

On top of all that, mothers on maternity leave often carry a sense of anxiety about their careers, wondering if they’re falling behind.

Raising a child alone is unbelievably tough for women (I hope this doesn’t sound patronizing—if it does, I sincerely apologize). That’s why I truly believe men should step in and support them as much as possible.

When I ask, “Do we need paternity leave?” I’m questioning whether it’s necessary as a formal system. In other words, should there be a policy where the government steps in and says, “While you’re on leave, we’ll pay your salary so companies, don’t worry—your employees can take time off”?

That’s the kind of system I’m referring to here.

岸田総理のメッセージ/Prime Minister Kishida’s Announcement

先日岸田総理が男性の育休期間中の手当て8割支給というの鼻高々に発表されてましたね。いわゆる「育児休業給付金」の水準引き上げです。

今は約6.5割なんで、大幅アップと言っていいでしょう。これは給料ではないので社会保険とか所得税が免れます。たとえ育休を取って勤務しなくとも手取り額的には働いている時と休んでいる時とで収入はそれほど変わらないというのが大きなミソのようです。

だから、

男性のみなさんもっと育休とって、奥さんに寄り添って、それでもってもっと子ども作ってね、これ以上少子高齢化進むとまずいんだよ。

ってのが政府のメッセージだと思います。

でもこれって私はとても疑問です。

最大の疑問は

1.その手当の財源はどこからなの?

2.そもそも育休を取れるような会社に勤めてる人って既に人並み以上に豊かなんじゃないの?

3.財政出動するのであればそんなことすら考えられない環境の人たちにすべきでは?

4.国が出してくれるんだから僕たちはそんなこと考えなくて利用したら良いの?

疑問だらけの制度です。

The other day, Prime Minister Kishida proudly announced an increase in paternity leave benefits to cover 80% of earnings. This refers to a raise in the “Childcare Leave Benefits” provided during parental leave.

Currently, the benefits stand at about 65%, so this is quite a significant increase. Since this is classified as a benefit and not a salary, it’s exempt from social insurance contributions and income tax. The key point here seems to be that even if you take leave and don’t work, your take-home income won’t be much different from when you’re working.

The government’s message appears to be:

“Hey, men, take more paternity leave, support your wives, and while you’re at it, have more kids! If the birthrate keeps dropping and the population keeps aging, we’re in serious trouble.”

But honestly, I have a lot of doubts about this.

My Biggest Questions

1.Where is the funding for these benefits coming from?

2.Aren’t the people who can afford to take paternity leave already doing relatively well financially?

3.If the government is going to spend money, shouldn’t it be directed toward helping those in environments where they can’t even consider taking leave?

Since the government is footing the bill, should we just take advantage of it without thinking too much about the broader implications?

This system raises more questions than answers for me.

なぜ育休制度が必要なのか/Why Is a Parental Leave System Necessary?

先ず、軽く厚労省のページから数字を。

“男性の育休取得率は2021年度でわずか13.9%、しかもその内2週間未満が約50%だった。”

それに対して総理は、その育休取得率を25年度に50%、30年度に85%とする目標を打ち出した。

ドヒャー、4年で4倍。

どうして、そんな大風呂敷を広げたのか?

現在の日本人の労働時間があまりに長時間でその結果、男性が子育てに参加する時間が取れないからです。ここにこそ最大の問題があります。

厚労省のデータによると20代から30代の男性の平均労働時間は週50時間から55時間が中央値です。

仮に少ない方の50時間としても1日10時間労働です。

それに首都圏の場合には平均通勤時間が往復2時間、睡眠時間を7時間と考えると、10+2+7≒19hとなり合計19時間。

1日24時間のうちわずか5時間が子育てに向き合える時間となります。(当たり前だけどこれは真面目なお父さんの場合、付き合いだ趣味だと言って寄り道するお父さんもいます。)

そんな状況ですから、仮に男性が育休を取らないと女性は妊娠出産後ほぼ一人で子育てをしなければならないことになります。

これじゃー子どもなんて作ろうと思わないし、ダンナ会社休んで育児手伝ってほしーな、しかしそれで給料減るのもやだなーってのが本音でしょう。

Let’s start with some quick stats from the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare (MHLW):

“In 2021, the paternity leave uptake rate for men was only 13.9%, and about 50% of those who took leave were back to work within two weeks.”

In response, the Prime Minister has set some ambitious targets: a 50% uptake rate by 2025 and 85% by 2030.

Wow—quadrupling the rate in just four years!

Why roll out such an ambitious plan?

The biggest issue lies in the excessively long working hours of Japanese workers, which prevent men from actively participating in child-rearing.

According to MHLW data, the median working hours for men in their 20s and 30s range from 50 to 55 hours per week. Even taking the lower end—50 hours—that’s 10 hours of work per day.

Now, add an average round-trip commute time of 2 hours in the Tokyo area and 7 hours for sleep, and we get:

10 + 2 + 7 ≈ 19 hours.

That leaves just 5 hours in a 24-hour day for anything else—including time for childcare. (And that’s assuming he’s a devoted father. Some dads spend that time on after-work drinks or hobbies instead.)

In such a situation, if men don’t take paternity leave, it leaves women to handle nearly all child-rearing alone after pregnancy and childbirth.

No wonder people hesitate to have kids in the first place!

It’s probably a common feeling: “I wish my husband could take time off from work to help with the kids. But then again, I don’t want his paycheck to take a hit either…”

だけど、育休取得が増えれば増えるほど財政は苦しくなり、一方で国力も落ちるよ。

But the more people take parental leave, the more strained the public finances become, and at the same time, the nation’s overall strength declines.

そんなところに颯爽とあの笑顔で登場したのが岸田首相でした。

僕が来たからもう大丈夫。育休とって会社休んでも良いんだよ、給料は国が手取り額10割保障するからね、さ、子ども産んでちょうだい、育ててちょうだい。

一見国民のことを思って言っているように見えますが、八方美人的だし、問題の先送りのように思えます。

総理の示した目標値である育休取得率を額面通りに25年度に50%、30年度に85%とすると、国民が育休を取れば取るほど財政は苦しくなっていきます、働かないのに国庫からお金はどんどん出ていくからです。

一方で育休を取るということは働かないということですから、労働生産量、労働生産高ともに落ちるので国として貧しくなっていきます。

国が貧しくなれば当然のようにそのしわ寄せは国民にきます。

And then, as if to save the day, here comes Prime Minister Kishida with his signature smile. “Don’t worry, I’m here now. It’s fine to take paternity leave and take time off work. The government will fully guarantee 100% of your take-home pay. So, go ahead—have children, raise them!”

At first glance, it seems like he’s thinking about the well-being of the people. But to me, it feels overly diplomatic, like he’s just trying to please everyone while kicking the real problems further down the road.

If we take the Prime Minister’s proposed paternity leave targets at face value—50% by 2025 and 85% by 2030—the more people who take leave, the more strained the government’s finances will become. Why? Because the national treasury keeps paying out, even though these individuals aren’t working.

And when people are on leave, they’re not contributing to the workforce, which means both the volume and value of labor output decline, ultimately making the country poorer. And when the country grows poorer, it’s only natural that the burden eventually falls on the citizens themselves.

https://www.gender.go.jp/about_danjo/whitepaper/r05/zentai/html/zuhyo/zuhyo00-20.html

育休取れる人と取れない人がいることの問題。

The Issue of Those Who Can Take Parental Leave and Those Who Cannot

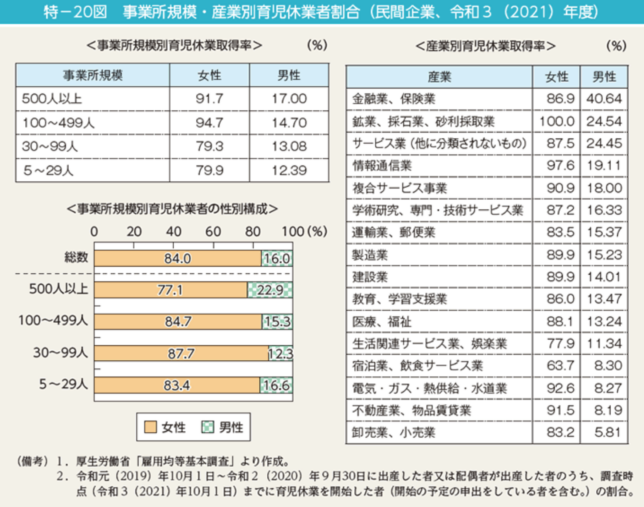

上のグラフを御覧ください。

男性、女性に関わらず育休が取れている取れていないには大きな格差があることが見て取れます。

育休が取れる会社などはいわゆる大企業だし、業種も金融・保険・サービス業とかたよっています。逆に取れない業種はいわゆるエッセンシャルワーカーと言われる人たちが勤める企業です。

私たちは彼らにこそ男性の育休とってほしいと心のなかでは思っていませんか?

であれば、企業規模も大きく、財政的にも余裕のある企業は男性の育休は大いに奨励しながら、その間も国の給付に頼るのではなく、企業として給料を払い続けるべきだと思います。

ここは民間企業としての矜持を示してほしいのです。そうすれば、国のお金は育休なんて取りたくても取ることのできない人たちに回していくことができます。

Take a look at the graph above.

You can clearly see a significant disparity in access to parental leave, regardless of whether we’re talking about men or women.

Parental leave tends to be available in large corporations, particularly in industries like finance, insurance, and services. On the other hand, those unable to take leave often work in industries associated with so-called essential workers.

Don’t we, deep down, want these essential workers to also have the opportunity to take paternity leave?

If that’s the case, then large corporations with ample financial resources should not only actively encourage men to take paternity leave but also continue paying their salaries during that time instead of relying on government benefits.

This is where private companies need to step up and demonstrate their sense of responsibility and pride. By doing so, the government’s funds could be directed toward those who desperately want to take parental leave but cannot.

そもそも育児は一ヶ月じゃ終わらない。/Parenting Doesn’t End in a Month

子育てされた方であればおわかりと思いますが、育児なんてのは1ヵ月で終わるわけもなくましてや平均的な2週間とって一体何ができるのか。

たとえ、育休を1ヵ月取ったところでそこで子育てが終わるわけではないですね、ましてや2週間程度取る人が100%になったところでそれが何になるのでしょうか。

もっと根本のところから変えていかなければならないし、そのためには働きかたそのものにメスをいれ、より豊かな労働環境を作っていかなければならないのではないでしょうか。

そのためにはお金が必要で日本人もっと働かなきゃダメですよね。

コロナ禍が襲った3年前、徐々に在宅勤務が増え政府も在宅勤務70%なんて政府目標を出してましたが、もう今はそんな数字は聞かないどころかテレワークやリモートワークという言葉すらあまり耳にしなくなりました。

通勤はすっかり何もなかったかのように元に戻りました。

これが唯一はたらき方を変えるチャンスではあったと思いますが長年の習慣というのは恐ろしいものです。

Anyone who has raised a child knows this—parenting doesn’t magically end in a month. So what can you even accomplish with the average two weeks of paternity leave?

Even if someone takes a full month of leave, it’s not like the work of raising a child is over at that point. And if 100% of fathers started taking just two weeks of leave, what real difference would that make?

We need to tackle this issue at its roots. That means making fundamental changes to how we work and creating richer, more supportive work environments. To achieve that, we need resources—money. And for that, we Japanese need to work harder.

Three years ago, when the pandemic hit, we saw a gradual shift to remote work. The government even set a goal of 70% adoption for telework. But now, that figure is hardly mentioned anymore. In fact, you rarely even hear the terms “telework” or “remote work” these days.

Commutes have quietly gone back to the way they were, as if nothing ever happened.

I believe that period was our one real chance to fundamentally change how we work. But as it turns out, old habits are hard to break.

この通勤という習慣はイギリスを中心に18世紀後半から19世紀初頭にかけて起きたいわゆる産業革命によってもたらされました。蒸気機関や紡績機械などの発明や工場制度の確立、交通・通信技術の発展などが進み、農村から都市への人口移動や、生産手法の劇的な変化などが起こりました。その結果、世界中の都市に通勤という習慣が生まれました。日本においては産業革命は遅れてやってきましたから始まったのは明治維新を待たなければなりませんでしたが、それから150年の間にすっかり私たちは通勤を当たり前の習慣として受け入れました。それがコロナによって3年間中断されていましたが、この150年の習慣の重みは結構根強いですね。通勤風景はコロナ前にすっかり戻ってしまいました。

しかし、今、テレワーク以上に働き方を変えるであろう新手がやってきましたね。

今年に入って、IT業界の最大のニュースはLLM(ラージランゲージモデル)によるChatGPTの登場だったかと思います。これによって18世紀から19世紀にかけて起きた産業革命よりも革命的な革命が起きるのではと私は思っています。しかも前回の産業革命のように50年もの歳月はそこには必要ないでしょう。

前回の産業革命は労働者を都市に集め工業製品を生産しそれらを輸送するための交通網を発展させそれに人間も乗っかるような形でした。

しかし、今回移動するのは物ではなく情報であり知性なので必要なのはネット網であり身体的な移動はそれほど求められません。

今度の産業革命は何をどうもたらすのかまだ見えていませんが、それによって私たちのはたらき方が全く変わってしまうのは確実だと思います。前の産業革命ののち通勤という習慣が生まれ、それが男性の育休問題を起こしたように、また何かをもたらすのでしょう。ぜひそれが子育てへの恩恵であってほしいと願います。

The Commute: A Legacy of the Industrial Revolution

The habit of commuting was born out of the Industrial Revolution, which began in the late 18th to early 19th century, primarily in Britain. The invention of technologies like the steam engine and spinning machines, the establishment of factory systems, and advancements in transportation and communication brought about massive changes. Populations migrated from rural areas to cities, and production methods underwent dramatic transformations. As a result, the practice of commuting emerged in cities worldwide.

In Japan, the Industrial Revolution came later, only taking root after the Meiji Restoration. But over the 150 years since, commuting has become an ingrained part of our lives. While the pandemic interrupted this routine for three years, the weight of that 150-year-old habit is deeply entrenched. Now, the familiar commuting scenes have fully returned to their pre-pandemic state.

However, a new force has emerged, one that could transform how we work even more profoundly than telework.

The biggest news in the IT industry this year has undoubtedly been the rise of LLMs (Large Language Models), spearheaded by the debut of ChatGPT. I believe this innovation could trigger a revolution more groundbreaking than the Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries. And unlike that earlier revolution, this one won’t take 50 years to unfold.

The previous Industrial Revolution centralized workers in cities, produced industrial goods, and developed transportation networks to move those goods—and people along with them. But this time, what’s moving isn’t physical goods; it’s information and intelligence. What we need now are networks, not physical transportation, and the necessity for bodily movement is far less.

While it’s still unclear what this new revolution will bring or how it will reshape our lives, one thing is certain: it will radically change how we work. Just as the last Industrial Revolution introduced the habit of commuting, which eventually led to issues like the challenges of paternity leave, this new revolution will bring its own consequences.

I sincerely hope that one of those consequences will be meaningful benefits for parenting and child-rearing.

根本的な問題は何?/What’s the Fundamental Issue?

そもそも解決すべき問題は長時間労働だし、長時間通勤です。

この二つを短くし労働生産性を上げていくことに注力するべきであって、会社を休みその分を育児に充てる考え方だと、労働生産量も額も落ちるし、つまり国のGDP下がるし、給付金のための税金の投入も増え、国自体がおかしくなってしまいます。

国自体がおかしくなれば男性諸君育休取ってちょうだいなんてそもそも夢物語になりかねません。

The real problems we need to solve are long working hours and long commutes.

We should focus on reducing these two factors and improving labor productivity. The idea of taking time off work and reallocating that time to parenting might sound appealing, but it ultimately leads to a drop in both the volume and value of labor output. This means the country’s GDP will shrink, tax spending for benefits will increase, and the nation itself could spiral into dysfunction.

And if the country starts to fall apart, the whole idea of “Men, please take paternity leave!” could end up as nothing more than a pipe dream.

夫婦が子育てに参加できるような環境を作っていかなければ。

Creating an Environment Where Couples Can Participate in Parenting

単純に休みだけ増えれば、労働生産量が落ちてしまい国の力の大元であるGDPが落ちてしまう。

少ない時間で労働生産性を上げていくような働き方にしていかなければ、この国はますますまずい状況になっていくのではないでしょうか

もしも取るのであれば最低でも1年は取るべきでしょう。仮に一ヶ月の育休を取ったとして、31日めから育児がなくなるはずないんです。

でも1年取れれば保育所も待っていてくれます。

そうであれば1年とっても所得が保証され、キャリアも中断せず、それでなおかつ労働生産も落ちないようにすべき根本的な対策に舵を切るべきでは。

異次元の少子化対策と言いながら、手当を6.5割から8割に増やしてるだけじゃんって。

それでは恒久的な夫婦の子育て参加にはならないでしょう。

We must create an environment where both partners can actively participate in raising their children.

Simply increasing time off will only result in a decrease in labor output, which directly impacts GDP—the foundation of a nation’s strength.

Unless we shift to a working style that increases productivity within shorter hours, this country is headed toward an increasingly precarious situation.

If parental leave is to be taken, it should be for at least a year. Taking just one month of leave doesn’t mean parenting responsibilities vanish on day 31. But if a parent takes a full year, daycare centers will be available to support them when they return.

In that case, we should steer towards fundamental measures where parents can take a year off with guaranteed income, uninterrupted career progression, and no drop in labor productivity.

The government calls these “unprecedented measures to combat the declining birthrate,” but all they’ve done is raise the benefit from 65% to 80%. That’s not enough to enable couples to participate in parenting in a sustainable, meaningful way.

根本的解決は、男性の可処分時間を増やすこと。

The Fundamental Solution: Increasing Men’s Disposable Time

と言うところでそんなところに国として税金を投入していただきたくないんです。中小零細であれば仕方がないです。大いに国の補助に頼りましょう。

しかし財政的に豊かな大企業は国に頼るのではなく、子どもが生まれた社員には有給をその分1ヵ月、1年と当てるべきではないかとそう思うわけです。

そうでなければ、悠々と10割もらって休んでいる大企業の人のために、汲々として働いている人たちの税金が使われることになるんじゃないでしょうか。

その男性育休の手当てを国が支払えるのも、私たちが税金を支払っているからなのですから。

This is why I don’t want public funds being used in this way. For small and medium-sized enterprises, it can’t be helped—by all means, let them rely on government support.

But financially strong large corporations shouldn’t depend on government aid. Instead, they should allocate paid leave—whether it’s a month or a year—for employees who have children.

Otherwise, we end up in a situation where taxes paid by hardworking individuals are being used to allow employees at large corporations to leisurely take leave with full pay.

Let’s not forget, the government can only afford to pay these paternity leave benefits because we are the ones paying taxes.

子どもは天からの授かりもの/Children Are a Gift from Heaven

お母さんの子育てが大変なのかどうなのかはそのお母さんの環境によるところがとても大きいと思います。実家の助けもなく歳も近い二人目の子育てに向かっている方と、実家の近くで一人目を出産し周りの人たちが世話をしてくれる環境ではそのストレスは大いに違うはずです。

また、夫が往復の通勤や残業でほとんど家にいない家庭と、在宅で仕事をしていて、いつでも子育てに参加できる環境でも大いに違ってくるはずです。

そんな恵まれた環境の人は「僕はそんなに大変じゃないから国の税金を使ってまでも育休は取らなくてもいい」そんなふうに考える人がいてもいいし、そういう人を雇用している会社は、そうであれば私たちの会社は国に頼るのではなく会社として給料を出すのでどうぞ休んでくださいといっても良いのではないでしょうか。

今の世の中は、制度としてできあがっているものをみんなが与えられた自分の権利として主張しすぎているような気がするんです。あえてもっとひどい言い方をすると、せっかく与えられてるんだから使わなければ損だという感覚。

でもちょっと待ってほしいんです、あなたは当たり前のように使えるかもしれないけれど世の中にはそうでない人はいくらでもいる。こういった制度の利用はそのような人たちにこそ譲るべきであって、そうでもない企業や会社員は自重して良いのではと思うのです。

理想かもしれないけど、いわゆる譲り合いの精神は子育てにこそ発揮されて良いのではないでしょうか。

ただ、そうすると利用しない企業は、男性の育休制度利用率の低いブラック企業のレッテル貼られちゃうかもしれませんね、ここも問題だと思います。

でも、そんなふうにみんなが支え合ってるんだって意識が生まれたときには少子化問題なんてのは自然と解決してしまうような気がします。

だって、子どもは天からの授かりものだってよく言うじゃないですか。

そしてその天は私たちのことをいつも見てくれているのですからね。

Whether or not parenting is challenging for a mother largely depends on her circumstances. For instance, a mother raising her second child close in age to her first, without help from her parents, would face significantly more stress than a first-time mother living near her family, surrounded by supportive relatives. Similarly, there’s a big difference between a family where the father is barely home due to long commutes and overtime, and one where the father works from home and is always available to help with parenting. For those fortunate enough to be in such supportive environments, it’s okay to think, “I don’t have it that hard, so I don’t need to take paternity leave funded by taxpayers.” And companies employing such individuals could say, “If that’s the case, we won’t rely on government support. We’ll cover your salary ourselves, so please take your leave.” It feels like in today’s society, people see government-provided systems as rights they’re entitled to use to the fullest. To put it bluntly, some may think, “It would be a waste not to use what’s available.” But let’s pause for a moment. Just because you can use these systems easily doesn’t mean everyone else can. There are plenty of people who don’t have the same access. These systems should be reserved for those who truly need them, and companies or employees who don’t fall into that category could show some restraint. It might be idealistic, but shouldn’t the spirit of sharing and consideration be most evident when it comes to parenting? Of course, there’s the risk that companies not utilizing these systems might be unfairly labeled as “black companies” with low male paternity leave utilization rates. That’s another issue we need to address. But I believe that if we can foster a collective awareness that we’re all in this together, the problem of declining birthrates might resolve itself naturally. After all, children are often said to be a gift from heaven. And heaven is always watching over us.

よくよく考えてみるとですね、こういった国が制度して与えているというか用意しているものをよくよく考えてみると、これは社会の公共財といっても良いものだと思うんです。公共財ですから国民みんなのものですよね。しかし、そのパイの大きさは限られてます。みんなが目一杯使えばたちどころになくなってしまいます。

そういう性質のものであると捉えることができるのであれば、やはりそれは使わないで遠慮しておくというのも徳の一つではないでしょうか。そしてそれを逆方面から見ていくとより際立ちます。

企業はよく寄附行為というのを行います。

私たちも赤十字的なものに会社としてお金を寄付したりしたことがありました。

この「寄附という行為」と「制度を使わないという行為」は結果として同じことをしてるんじゃないかと思うんです。寄付は公共財を増やす行為です、制度を使わないのは公共財を減らさない行為です。ともに私たちが意識して行っていかなければならない行為ですね。

When you think about it carefully, the systems that the government provides or prepares for us can be considered public goods. Public goods, by definition, belong to everyone in society. However, the size of that pie is limited. If everyone uses it to the fullest, it will quickly be depleted.

If we view these systems as public goods with such limitations, isn’t it also a virtue to refrain from using them unnecessarily?

This perspective becomes even clearer when viewed from another angle.

Take, for instance, the charitable acts that companies often engage in. My company has also made donations to organizations like the Red Cross.

I believe the act of “donating” and the act of “not using a system” ultimately achieve the same outcome. Donations increase public goods, while not using a system preserves them. Both are actions we should consciously engage in.

このブログ記事を書いてからもう2年近くが経ちますが、いよいよ今年の4月から給付金は80%に上がるようです。そうすると社会保険料などが免除されるのでほぼ手取り額は変わらないようになると思われます。

私たちの会社にも外国籍の方が増えてきたので、英訳を加え2025/01/08一部更新しました。

ただやはり、私は完全なテレワークであれば男性の育休は取らなくても良いのじゃないかとそう思います。育休という制度は利用しなくとも、新しい命が誕生したのだから子どもを中心とし、仕事はいい意味で適当にやってくれたら良いのです。当然欠勤でもなんでもないので給料は通常通りに支払われます。

給付金なんていらない!

なんか強がりを言っているみたいですが、そんな会社があっても良いと思うのです。

ただ、ここは誤解のないように述べておかねばなりませんが、育休取得ができる人の取得を会社として拒むものでは決してありません。特に今年度4月からはほぼ手取り額は変わらなくなるので、会社に気兼ねなく取れる制度はとても魅力的かと思います。

一方、出勤がある方であれば育休制度はできるだけ利用して育休は取らなければいけないと思います。強くそれは思います。お母さんが1人で子育てをするのはいくら環境に恵まれていたとしてもかなり困難だと思います。

以前も書きましたが、男性の育休が必要なのはそれぞれの環境によるところがとても大きいと思います。一人目の子なのか二人目か。全く手のかからない子もいれば両親ともにノイローゼになってしまうような子もいます。家族と同居なのかどうか、住まいの環境はどうなのかなどさまざまでしょう。

それらを一律に扱うのは、制度とはそういうものですが、どうなのかと思います。これは平等(equality)と公平(equity)の問題でもありますね。

2025/01/08追記

It’s been nearly two years since I wrote this blog post, and finally, starting this April, the benefit rate will increase to 80%. With social insurance premiums being exempted, it seems that take-home pay during parental leave will remain almost unchanged. As the number of foreign nationals in our company has increased, I have added an English translation and made partial updates on January 8, 2025.

However, I still believe that if one is working entirely remotely, there might be no need for men to take parental leave. Even without utilizing the parental leave system, since a new life has been born, it’s acceptable to prioritize the child and approach work with a flexible attitude. Naturally, this wouldn’t count as absenteeism, so the salary would be paid as usual.

No need for benefits!

It might sound like bravado, but I think it’s okay for such a company to exist.

However, to avoid any misunderstanding, I must state that as a company, we would never refuse an employee’s request to take parental leave if they are eligible. Especially with the upcoming changes in April, where take-home pay will remain almost unchanged, the ability to take leave without hesitation is quite appealing.

On the other hand, for those who need to commute to the office, I strongly believe that they should utilize the parental leave system as much as possible. I firmly think so. No matter how favorable the environment, it is quite challenging for a mother to raise a child alone.

As I mentioned before, the necessity of men’s parental leave largely depends on individual circumstances. Whether it’s the first child or the second, some children are easy to care for, while others can be so challenging that both parents become exhausted. Factors such as living with extended family or the living environment also play a significant role.

Treating all these situations uniformly is the nature of systems, but I wonder if it’s appropriate. This also touches on the issue of equality and equity.

Additional note as of January 8, 2025.

今日のアサカイは再びこちらの男性育休の話題でした。男性のメンバーからもうまもなく自分に二人目のベイビーがやってくるので、育休どうしようかな、皆さんどんな考えしてますかっていう話題の提供でした。

意見は活発に出ました、出ましたが誰の口からも「社会」という言葉が出てこないのです。

どうも対社会みたいな視点での話しが出てこないのです。自分や家族の視点からの意見ばかりなのでこれはまずい……。

うーん、あんまり僕がしゃべるとよくないよなーと思いましたがどうにも我慢ができない、これだけは言わせてーって感じで一言申し上げました。

「男性の育休取らなくて良いよってーのは、社会貢献ですよ、社会への寄付行為なんですよ」と。

発言の後、ちょっと画面見ながら待ちました。ん?やっぱり通じてないかな?

と思ったその時、別の男性メンバーが答えてくれたのですが、正解です!そうですそうですきわめて論理的に考えていけばその答えが出るのです。

そして会社は何のために存在するのでしょうか?

どこまでいっても社会のためだと私は考えます、そしてその社会は同心円状に広がっていてその一番内側にいるのが私たちなのです。私たちが私たちだけで存在しているわけではないのです。

2025/03/12追記

Today’s Asakai once again revolved around the topic of paternity leave. One of our male members, who is expecting his second baby soon, raised the question: “What should I do about taking paternity leave? What do you all think?” Discussions were lively—plenty of opinions were shared. However, not a single person mentioned the word “society.” It seemed that no one was approaching the topic from a societal perspective. Instead, all opinions were centered on the individual or family level, which felt problematic… I thought, “It wouldn’t be good if I talked too much,” but I just couldn’t hold back. I had to say this one thing: “Choosing not to take paternity leave is an act of social contribution, a donation to society.” After making this statement, I paused and watched the screen. Hm? Maybe they didn’t quite get it? Just as I started to wonder, another male member responded—and he got it right! Exactly! If you follow the logic thoroughly, you arrive at this conclusion. And why does a company exist in the first place? I believe, no matter how far you go, it ultimately exists for society. And that society expands outward in concentric circles, with us at the very core. We do not exist in isolation. Updated on 2025/03/12

先に私たちの会社の副業あるいは企業全般の副業に対する考えの変遷をこちらに示しましたが、この記事の男性の育休に対しても同様だと考えています。

男性の育休は個人的にも会社的にも大いに賛成だしそれを頑張って進めていかないとおそらくこの日本はダメになってしまうかと思います。男性の育児参加は時代の流れであり必須です。

私が先に述べたのは私たちの働き方の上での理想であり、それを補完するための思想的意味合いのものでした。

どのような思想かと申しますと、ある方が教えてくれましたがそれはこのブログでも度々投稿している報徳思想を形成する四つの柱「至誠」「勤労」「分度」「推譲」のうちの一つである推譲を表しているのではと。

なるほど、その通りですね。

「推譲」とは分度の結果手元に残った当時で言うと米や資源、富を他者や次世代に回すという行為を指すのだと思います。

現代の制度で置き換えると、国の育休給付金も限られた財源(予算)という意味で「共有資源」ですからそれにはできるだけ手をつけず他者や次世代に残しておこうと言う思想です。

しかしそれを会社の代表が強調してしまうと、善意が制度化されてしまい、個人の自由な選択が道徳的な義務にすり替わる危険があることに気付かされました。

本来の「推譲」は、自発的にやるからこそ徳であって、他人から「そうすべき」と言われた瞬間に、それは徳ではなく同調圧力になりかねません。

理想や思想は一旦手元に置き、まずは自らがそれを実践していく。それこそが理想や思想を実現する手立てなのではと思います。

2025/08/10追記